In one of my rare excursions into gaming, I recently finished 'Thief: The Black Parade'; a full game of fan-made missions for the 199-something “immersive sim” (before we had that phrase) – ‘Thief: The Dark Project’.

I originally conceived this article as an essay on the concept of ‘Butterfingered Infinity’; something about the uses and limitations of ‘natural language’ as compared to, and revealed by, a complex virtual simulation like Thief.

In the end it became just the meat in a thief burger, with the start being a distaff review of a much-reviewed game and the end being an odd mix of suggestions for D&D.

The Thief-Review is below.

The essay on Butterfingered Infinity in the middle.

Thief’s Lessons for D&D at the end.

Why Thief is Good

Thief was a nearly pure-stealth simulator which, through talent, work and luck, coalesced into perhaps the best stealth game. Other reviewers have talked about why this is in more depth than me; its engine, built specifically around shadow, its first-person nature, its exquisite and carefully engineered sound design, and the integration of that sound into its level design and its relationship with violence and the vulnerability of its main character.

[A brief digression on stealth and violence; they don’t mix. Stealth and murder, (or, if you are batman, stealth and a beating), make an intoxicating combination, such that, if you build a complex immersive sim, where both stealth and violence are available, any sane character build will naturally coalesce around some kind of stealth-archer or stealth-assassin - as this is optimal in-game and feels powerful to the player.

Then, if the game wants to make the now hugely-empowered player behave in a purely-stealthy fashion, to fit the theme and feel of the game, they need to add in extra-diegetic elements, rulings, 'points*' and so on in order to make the player-character behave 'stealthily' and, in the words of one reviewer; ‘you are being stealthy to protect the NPCs from you, not to protect you from them’.

This is a mistake no game in the Thief series ever makes, since the Player Character is always, by Protagonist standards, insanely vulnerable, and sword fights are a nightmare. The structure of the game, without extra-diegetic elements, makes you want to play as a thief. It’s a game where you can snipe people in the back of the head, but won't want to as it would feel unprofessional.

{A digression with a digression on ‘points’; There should be some neo-OSR ruling about points being the opposite of gold as, just as xp for gold is almost always good and feeds dietetically in so many ways into the game, there is a kind of reverse of that, in which, as soon as 'points' are involved in anything, it almost always gets worse, though the means and method of how that happens will vary greatly.}]

The Black Parade

Based on the engine for the original ‘Thief’, Black Parade is large and complex enough to be a fourth game in the franchise. For free. Which is, I think, larger than any of the other games, and might be the best one? At least I think it has more consistently high level design than any other version of the game.

Its staggering really that a small number of talented people could collaborate for so many years

to produce something both so massive, and so exquisite. Thief was always a distantly OSR-ish game and its fan-mission community is even more so. For ‘The Black Parade’ Melan gets a mention in the credits!

The Paradoxes of Thief Level Design

What defines Thief games more than anything else is level design and it is here that some of the interrelationships between Thief and the OSR are brought into focus

Fear, Desire, Exploration and Investigation

In 'Thief', you think like a thief. You are vulnerable and can be killed easily, so you carefully watch, and LISTEN, to the environment, constantly checking for threats. You also hide relentlessly, moving carefully from shadow to shadow, cursing electric lights and marble floors. Your only real safety is the darkness and so you cling to it instinctively, even when there is no tangible threat, because there might be one; a wandering guard or servant, or something else.

So fear and vulnerability ensure you deeply and constantly search, investigate and utilise the environment, and when these are naturalistic environments, you are deliberately navigating them in a way that feels ‘inverse’ and therefore a little cool. You might be in a kitchen and, instead of doing Kitchen things, be searching for fragments of shadow in the light coming from the stove, creeping behind shelves etc.

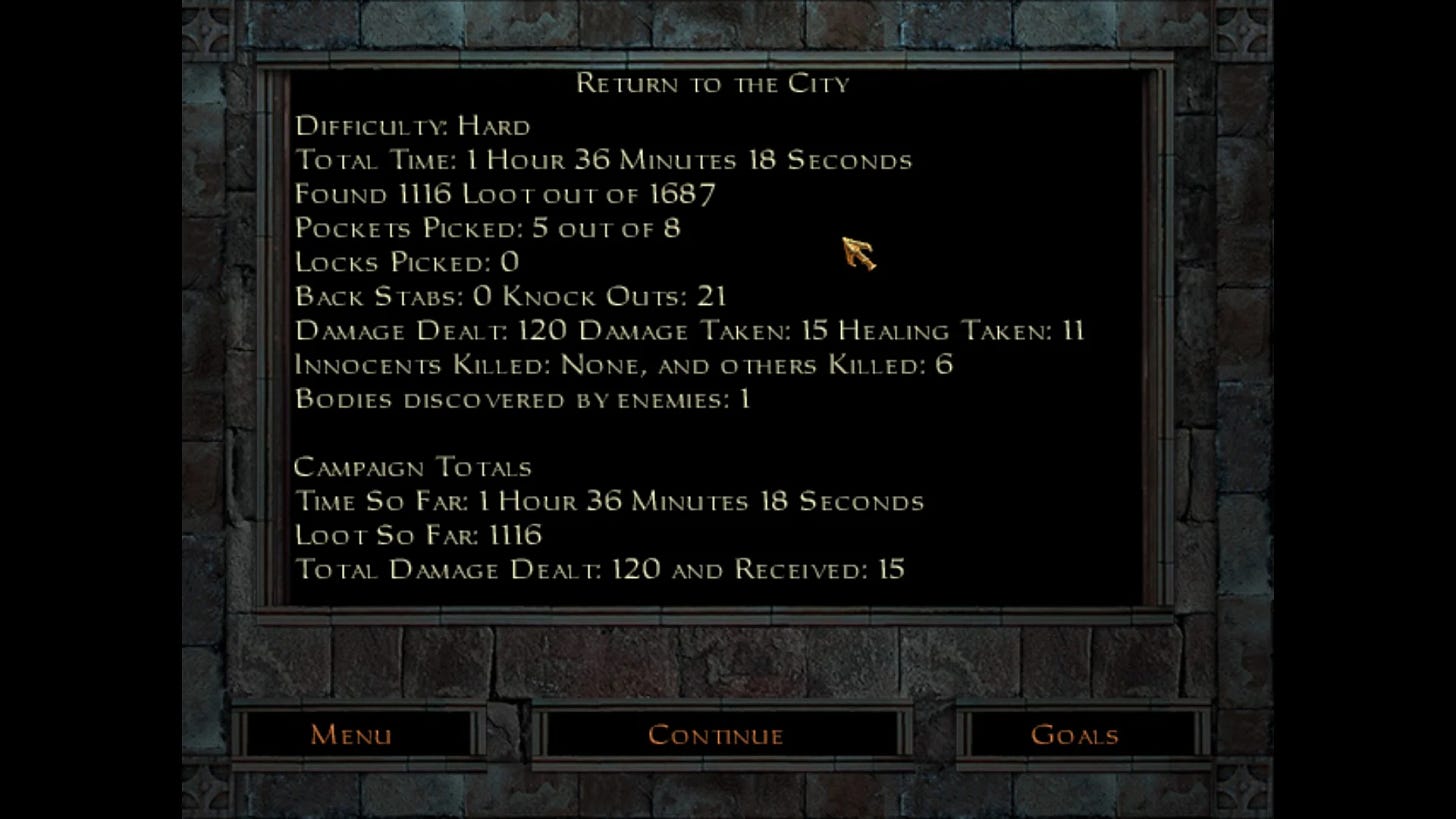

You are a Thief, you want to steal not kill. There are no points for killing and increasing the difficulty of the game (usually) only increases the conditions of play, not the substance of the game itself. Maximum difficulty means getting all of the treasure without killing and sometimes even without harming anyone. {Thief does mix this up somewhat with the easy availability of the blackjack, with which you can "knock people out" but only if you catch them unawares}.

Desire keeps you fixated on that shiny artefact on the dresser, and carefully avoiding anything sensate or alive. Guards walk regular routes and chat with each other, and this means a chunk of Thief is listening for and measuring the movements of others, so you can avoid them. In almost every case you are searching for a way around anything dangerous. You are continually mapping the physical space in your head and also the routes and movements of any living thing within that space.

The Music of Pseudo-Naturalism

The best thief levels are pseudo-natural. You can intuit things about them from their nature and then investigate based on those intuitions, and sometimes be right, which makes you feel very clever stately home will have a kitchen and cellars, a Cathedral will have a belltower, etc. They are also physically distinct and separate from the surrounding area.

The urban slum levels are slightly less-perfect because the pseudo-nature of the level becomes more obvious; there are unopenable doors and inaccessible areas; PNG’s of doors on buildings that rim the play area. Though you can still try opening them, and discover from the games response if they are actually just PNG doors, or would respond to a lockpick or yet-to-be-found key. A handful will turn out to be functional, as you will discover when you find the right thing to open them, or pop up from the other side after dicking about in a sewer for hours.

Still, it’s curious that in D&D there are no unopenable doors, or at least, there are no simulated doors. The play area, in theory, expands outwards forever, and in practice, only becomes misty, general and improvisational as you move out of whatever the DM has thought about already, (but come back next week and the details will have sharpened up a lot).

But, just like Dungeons’, Thief levels are almost never purely naturalistic. Firstly; they are simulated environments, and can’t match the chaos or complexity of the real world, second; they have locked doors which need keys, sequences of actions needed to progress, certain pieces of intelligence which must be combined to succeed; they have paths, like flow-charts, which lace through these otherwise wide-open environments.

Still they are otherwise very wide open, with a large array of possible ingress points, secret routes and other possible access-ways that strongly reward exploration, investigation and, sometimes, cunning extrapolation from the logic of the depicted world. Nothing is quite as pleasurable in Thief as spotting a chimney, pipe or ledge, wondering if you can get to it, finding a way to, then realising you can find a way inside/across, then popping up somewhere you should never have been able to get to.

There are “weird” Thief levels too, set in ancient magical tombs, lost cities or supernatural netherworlds, but they are never quite as good. Great Thief levels exist at a near perfect synthesis of naturalistic play-space and toyetic, planned sequential-challenge environment. They are levels where the nature of the space provokes investigation and exploration, which it also rewards with naturalistic opportunities, where a complex adventure-flow runs through the pseudo-naturalistic space but where the space always gives opportunities for adaptation, evasion and incursion. A toybox with the lid half-open if you will.

Butterfingered Infinity

Thief is actively trying to give you an experience very like that of an AD&D Thief, and does so, in a curious mirror-view fashion, but the differences between a Thief in play in D&D, and a Thief in Thief, are interesting to consider.

Problem solving in D&D is often related to the concept of ‘tactical infinity’ due to the very wide-open nature of possible approaches to various problems, but its more like a ‘Butterfingered Infinity’ in which the Players can hold and use almost any imaginable, or describable, concept, but carefully, and with blunt inexactness. The infinity of the Word rather than the Vast but Finite potential of the Eye.

An Equation on the Utility of Blunt Infinity

A very rough pseudo-equation on the utility of words in roleplaying might be something like this;

[The Descriptive Power of Language] – [[(word concepts the DM actually knows) x [(The Speed of relation) + (what the Player Group can easily understand)]]

The Descriptive Power of Language

There are a lot of words. If you have enough time and a big enough dictionary, you can describe almost anything. It we assume the total potential of words, and look for things they absolutely cannot describe, there is not much, but here we enter paradox, because we are trying to use words to describe what words can’t describe.

(This is a problem which exists continually, as a faint umbra, which sometimes obscures and sometimes reveals, whenever we come to think about the things language can’t do, in almost any situation.)

But, so far as things that could be interacted with in a tabletop game, a computer game or any other form of simulation, let’s assume that words might be able to describe nearly everything necessary to know

How much the DM actually knows

The classic DM is a natural word-hound and Gygaxian Wunderkammer encyclopaedist. Not a few writers have named D&D as a font for their discovery and use of words, and the use of strange or novel words can, with limits, be a pleasurable aspect in itself in D&D.

Lets assume the DM knows a lot of words.

Speed of relation

We can describe anything if we have time. But technical, unfamiliar jargon, and highly precise measurements, as well as large numbers of things or elements, will all take time, which robs immediacy, and in some theoretical cases, perhaps a truly insane amount of time.

How much and how easily the players understand

For a concept to be useful, it has to be known to at least some of the players. A rare word-concept only the DM knows is a near-useless word-concept. It is the Player Group that must understand. I real terms this means, probably (?), at least two or three know it and can easily explain to the rest. If this happens many times in sequence, the game dies.

No-one is paying as much attention to the whole thing as the DM. Every individual has a totally different base capacity for imagining different things, so the words flow out, are half attended to

and when they are attended to, are understood differently by almost everyone. In effect, a DM has a relatively small ‘armoury’ of words and conceptual language which is strong, simple, descriptive and already mutually understood by almost everyone, from which they can take excursions into complexity, for short periods and specific problems, but which they always return to. We can think of this as the ‘verbal armoury’ or word-hoard of natural language. The aspects of spatial and physical situations that make up the meat and majority of D&D problem solving are those for which or conceptual language is already well developed and widely shared, and which can be imagined with ease by a wide variety of people.

So: being STUCK to something, being TIED to someone. Being BEHIND someone. Getting a LEG UP. In fact in terms of three-dimensional space, these are all things most of us did as children, which is why we understand them. For many of us who are not athletes or dancers, childhood was our first, last and by a large margin, greatest education in the nature of three-dimensional space and the language of physical problems remains that of the playground.

Responses to ‘The Limitations of Language’

I asked people on Twitter and Facebook about “things and situations you have experienced as a DM, which have proven really difficult to describe quickly and clearly using *only* spoken words?

(The classic is trying to describe a complex 3D environment to a bunch of people but I am interested in other examples.)”

The responses were very interesting!

Tim Samwise Seven Harper; “I sometimes struggle with describing natural environments filled with fantasy plants and animals. I always try to picture those scenes from Dark Crystal and that helps, or I default more toward real trees and plants as well as real life animals with a twist.

Big parties with hundreds of NPCs are always a challenge. I tend to use 3x5 cards with a few descriptive words on each NPC card.”

Yuri Zanelli; “PC's and other creatures' positions in their environment. Miniatures can help a lot with that, but I don't like to use them. My game tables tend to be already too crowded with maps, manuals, bottles, snacks, character sheets, dice, notepads and so on. I tend to use a quick sketch on a sheet of paper.”

Greg Benedicto; “Describing liminal elements in a scene WITHOUT drawing obvious attention to them.”

Jesse Rooney; “As a general rule, spacial relationships are much easier and faster to show then tell. Hence minis at the table. There are a number of times when playing theater of the mind that Ive pulled out a sketch pad to demonstrate who and what is where.”

John Enfield; “That's why I use gridded maps (either hand drawn or published), minis and occasionally terrain pieces. Having visual aids helps aid in describing environments.”

Ragnar Hill; “A good ambush because players always start squealing and panicking and then I get over excited.”

PARAMANDER @CravenSensation; “Mechanisms or devices made of many parts and monsters with complicated and alien anatomy. Even if each detail is relatively straightforward/easy to visualize, more details means higher potential for miscommunication + more attention required on the part of the players”

Derek Dees @NihilSineLabor; “Places with lots of shadows and light, not sharp contrasts, but layered or with partially obscured nooks and objects.

The Great Hall of Durin, as light broke through, but shadows still engulfed so much, for example.”

Bo Banducci @bo_banducci; “I’m struggling to remember one aside from the classic. Possibly when an NPC is lying to the players and I want to intimate this somehow without giving it away.”

Synthesis of Responses

I broke these down into a few large categories as a tool-of-thought, (with the usual effect that many real-life situations involve one or more categories, often in point and counterpoint.)

These provide a very brief idea-map of things with which ‘Words’ are especially butterfingered;

PLETHORALITY

“natural environments filled with fantasy plants and animals”

“Big parties with hundreds of NPCs”

“Mechanisms or devices made of many parts and monsters with complicated and alien anatomy”

We know about these things because we encounter them in life, and the Eye can show them to us easily and immediately – well, if not quite immediately, a scene or painting can give us a very quick general impression of a scene with many things of strange and novel quality in it, which the scanning of the eye-and-mind can ‘fill in’ very smoothly and fluidly, much faster than words could describe. When the eye works with the ear, they can combine, bind and represent a truly complex scene, in but a moment. Nature can present deep, immediate and novel interconnected complexity in-one. Words are slow, specific and sequential, happening one after another, and sometimes blunt. These are two forms of time in conflict.

Thief does well with some forms of ‘Plethorality’; its ‘big views’ where you teeter on a rooftop and get a nice ’Batman’-esque view of a highly vertical city, are exciting and poetic, and also useful as you start planning routes and investigating things with the eye. But Thief, like other virtual simulations, is strongly limited in the number of active, moving, identifiable, people and living things it has going on. Not quite as much as words, but a fair amount. They really eat programming power.

DIMENSIONALITY

“PC's and other creatures' positions in their environment”

“As a general rule, spacial relationships are much easier and faster to show then tell”

Or more prosaically; physical positioning and complex three-dimensional situations. But ‘Dimensionality’ sounds cooler.

In Thief the exact precision of a jump, climb or any other kind of movement, can be demonstrated in the substance of the world with deep subtlety and immediate precision. As in; “*this* I can jump on” to “*here* I can climb on to in a few moments”, “*here* I can climb up to, if I have equipment”.

The assessments are fluid, rapid and immediate, and this is a key part of the game. A patrolling guard is here and going this way, the next pool of shadow is over here and it will take me this long over the loud marble floor to get there. Then a climb of this length, then.. and so on.. Immediate, intuitive, fast.

A similar thing takes place with even small skirmishes, let along larger ones. Close physical positioning matters enormously and is very hard to communicate, accurately, and quickly, to a group. For this were sketch-maps made. Words alone have a butterfingered grasp on three-dimensional space.

LIMINALITY

“WITHOUT drawing obvious attention to them”

“A good ambush “

“Possibly when an NPC is lying to the players”

If problems with describing three-dimensional space were what I expected, and problems with ‘Plethorality’ were less expected, but make sense, then ‘Liminality’; secrets, shadows, deceptions and double meanings, in all ways, is an unexpected but quite beautiful problem to face.

It’s the illusionists problem. Or an actors problem. It seems to flow deeply from the situation of the GM or storyteller being the fount of both the reality as-a-whole, and of a deception within that reality.

A simple example; a scene in a visual narrative like a play or film. One character is lying. The actor and director want the audience to know they are lying. But the characters in the fiction are not supposed to know. How to solve this?

The answer depends entirely on the naturalism and subtlety of the fiction, its tellers and its audience. In a pantomime or cheesy melodrama, or a children’s play, its relatively simple, at least in concept; the moustachioed villain twirls their moustache and even cocks an eye at the audience, before saying “of course not! Bwahahaha!”.

The more naturalistic the drama becomes, the more complex and difficult the lie becomes to communicate. For a soap actor, a touch of archness, for a dramatic actor, a complex scene-setting and capturing by the director to prepare the way for the lie and leave the right kind of space around it, for a highly naturalistic ‘spy’ or intrigue drama – almost nothing maybe, but the tone and emotional volume of the scene must be low or even and this might suit best a modernist story where the audience just never finds out what the ‘truth’ is, or at least that ‘finding out’ isn’t central to what the story is doing.

For other kinds of secrets, they have been written about in depth by many people. How, and how often, to portray lying NPC’s, (my last read on OSR culture was that it was generally anti deceptive NPC’s because they were over-used, difficult to get right and crippled the PCs long term relationship with the game-world, leading to more murderhoboism than desired), huge debates and discussions on how to run investigations, (what does or doesn’t count as railroading), and clues, (the ‘three clue rule’),

“Places with lots of shadows and light, not sharp contrasts, but layered or with partially obscured nooks and objects.”

This was an especially interesting response as, I didn’t even mention Thief in the question, and literal complex environments full of layered shadow is the main thing that Thief does. They built an engine specifically for the game called ‘the shadow engine’.

Though this has strong elements of Plethorality, (the simultaneous number of things and their complexity), and Dimensionality, (its about a large, complex, 3D space), the fact that it is also about the revealed/unrevealed paradox at the heart of Liminality is fascinating to me.

Words find it hard to form reliable shadows and perceptible lies. Words can lie easily, but its very hard to get them to build a lie as-object.

Thief Lessons

Considering the deep differences revealed between the world of the Eye and Virtual Simulation, and the world of the Word, and social, conversational simulation, are there lessons we can actually learn from Thief about how to run D&D? Or are the worlds so different that we might even deliberately not try to transfer lessons between them, as they would lead to bad play?

Here are a handful of concepts from Thief and some comments from me on how and whether they might be useful in D&D.

‘Ghost Missions’

Even the hardest level of Thief doesn’t demand that you be seen by no-one, but high settings often insist you hurt no-one.

In D&D the effects of a difficulty setting or complex level can be delivered diegeticaly by a highly specific quest-giver; a priest or wizard wants something, and insists that you ‘kill no-one’ or ‘hut no-one’ or in extreme versions ‘are never seen at all’, performing a ‘perfect ghost’ Mission Impossible situation where the incursion takes place and no one ever knows it happened at all.

(Of course the Party get paid a lot for fulfilling these conditions.)

A mission like this already implies a very different kind of D&D, a quest based around planning, surveillance, mapping and intelligence gathering, and then a quick and complex incursion full of distractions.

Difficult to pull of in D&D, but far from impossible,

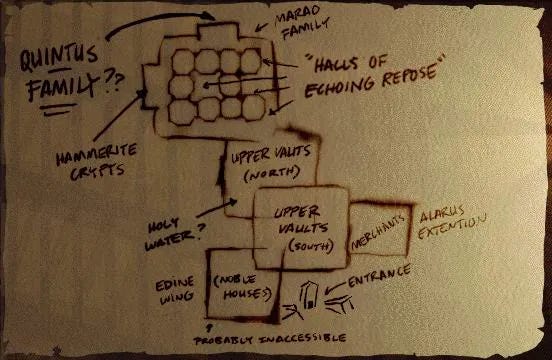

Sketchy Maps

Thief usually provides a map for each mission, and it is always a vague map. A sketch map with some useful information, but a huge amount of things it doesn’t tell you. Its usually enough for you to orient yourself in the play area and tell where the major sections roughly are, but absolutely insists you explore to find out what you need to know.

More sketchy dungeon and play area maps before games might be a good idea. Diegetic literal ‘sketch maps’ by previous thieves and adventurers. Maps good enough for you to form the bones of a plan, but clearly vague enough that you know going in that they won’t describe everything.

Monster PATROLS, not Monster ROOMS

God damn patrols are hard to manage in D&D without a lot of extra shit. No wonder monsters in D&D just really like their particular rooms. Its easy to simulate one or two from the encounter table, but a key element of Thief is timing the patrols. If patrols are regular or even mostly regular and predictable, then they become part of the environment you can learn about and plan for, and evading or subverting them makes you feel very clever as a player.

Arranging a full system of patrols for a dungeon or wizards tower would probably require an entire sub-system, but it might be fun to give it a try.

Clumsy Monsters with Keys

There should be more clumsy monsters carrying VERY OBVIOUS keys through the darkness. Big, dumb stupid but dangerous ogre guards who could easily one-shot a PC if they see them, with huge gold or silver keys hanging by their sides.

I’ve spoken at length before about how the big, dumb, dangerous ogre is the perfect low-level opponent for D&D.

Helix Views/Verticality

Dark-Souls helix-like atriums. In terms of dungeon design, this would be a game where there is more up and down. A dungeon arranged around a step well, inside a tower, down a mountains slope or similar.

Tempting Treasure

Would being able to SEE the treasure really have the same effect in a described game as in a virtual simulation?

For the main treasure, the idea is that, from most points of ingress, the main treasure the PCs are here to get is very visible, in a revered-panopticon style, but very hard to actually get to. I imagine it poised on the top of a tower, itself at the bottom of a vast cylindrical step-well or similar. You have to infiltrate all the way down, and then all the way up to get to it.

Thief has a lot of visually obvious, but very hard to reach, small and light treasures. So many in fact that it becomes hard to believe you have fit them all in your Thief-sack. Rather than having lots of mixed, hidden treasures in a dungeon-equivalent, what if instead, there were a small number of very gold and shiny very visible treasures, each in the centre of a complex, shadowy environment with guards patrolling, traps and other hidden obstacles, so it was easy to see where the treasure was, but very hard to work out how to get to it.

Discoverable Pseudo-False Alarms

A ‘ghost’ mission which demands perfect, or near perfect, stealth, (from a group), and pseudo-naturalistic patrolling guards, suggests a very binary result to mistakes. Which is; you make one, are discovered, alarm raised, mission a dead loss and now you are just fighting to get away.

In D&D you have a group who all need not to fuck up, and there is no quicksave, so some of the binary, complex and difficult challenges of Thief just won’t work.

An idea might be a way of artificially cancelling a general alarm. Or several ways, but each one only works once and is specific. This would be the equivalent of modern Thieves calling in to the police station with the password to tell them it’s a false alarm.

If the guards are big dumb ogres, and other things with less adaptability, like ghosts or constructs, then its not impossible there might be some kind of code or sign to get them to stop banging the Big Bell, blowing the alarm horn or whatever it is. Ideally, each of these methods would be completely different, and you would need to actually do the incursion and poke around to find some of them out. There would also likely be a max-usage, where, if you trigger the alarm three times, even if you have methods spare, even the Ogres are going to keep ringing the bell.

Visual Verticality

One of the most fun and engaging elements of a Thief level, if its pseudo-natural, is getting up really high, maybe somewhere you had spotted earlier, and climbing about, pulling a batman, looking down at the streets and tenements, the little guards scurrying about, and having a Cid Kagenou moment as you cackle to yourself about all the SHEEP below you!

For all the reasons give above in ‘Plethorality’ – this would be hard to make use of.

One method would be to combine the ‘Coms Snails’ idea below, with an ‘Eagles Perch’ position. Some hidden spot far above the play area with a big view that allows one person to sit there and whisper information to their fellow PCs as they buzz about below, each on their individual missions.

Comms snails

My old teen players got a bunch of silver-shelled telepathic snails and ended up using them as in-ear comms. In a Noisms game, we tried using psychic shrimp as a radio base in a similar way.

Why? Because comms are super-useful in D&D and once you have seen them in a film youjust naturally want to use them in group mission situations.

I know this is CRINGE as FUCK from a low-fantasy OSR perspective, BUT – it’s so deeply and desperately useful in doing meaningful physical GROUP stealth storytelling and problem-solving. It turns a knockabout fiasco into a heist.

For a purely-stealth mission where you actively don't want violence to happen, having the party split up is actually good it makes much less sense if they are all together, huddled together as a ‘stealthy gang’?, since stealth as a group always starts to feel more ridiculous than is useful. The social dynamics of play push against it and a tragedy of the commons situation happens where one impulsive player ends the mission.

Around the table, everyone can hear everything the everyone is saying and doing, so the extra-dimensional player-entities that pilot the PCs always have more of a global awareness than the PCs themselves, which, even with very disciplined play, often communicates itself to the PCs via shadowy tubes.

Allowing Comms-Snails for stealth-only missions might actually be a good idea that would improve play. Perhaps the stealth-obsessed wizards who hired you will loan them out.

Less-Lethal Falling

In these levels with-verticality, there should be more falling, and it should be less lethal. More bits where you fall into water, or something similar, but it doesn't kill you, and you end up at a different spot in the dungeon, separated from the group, and can explore and maybe find new routes to what you want, or just to link back up.

If being noticed is a fail state, then non-lethal separation is more interesting in play than HP loss.

Sound-Encounters

I think Brendan and others (possibly many others), have considered this will the ‘overloaded’ encounter die, but more encounters when you things or people coming, would be interesting.

In standard D&D being surprised is a reasonable punishment for dicking about and not paying attention, but in a stealth-only game, the threat of being discovered is more useful – the PCs have maybe one or two actions to hide or try something.

Stealth via Diegetic Sound

This isn’t directly from Thief, but I do think it would be a fun idea for stealthy D&D, which is; the sound you make around the table is the sound your character is making in the game.

So, if you want your PC to be stealthy – SHUT THE FUCK UP, and get WHISPERING! I think this would be a fine addition to the game. It would give all PCs access to some form of silence, and would encourage the players to actually fucking concentrate and think for once in their lives.

The ‘Mission Turnabout’

One possible useful import from Thief might be the ‘turn’ that happens in a lot of missions, for its is a way of involving liminality and deception that might be useable in D&D.

The classic ‘questgiver turns on you when you are done’, is rightly abjured in OSR circles, for reasons well-known. (Although Thief, does in fact use this trope a lot). But the idea of a delve having a clear set of objectives, and then, right in the middle of the adventure, something is discovered or something changes, and suddenly the goals and nature of the mission change, and change a lot, leaving you to improvise a new plan and work with the same space you had previously, but towards entirely new goals, this could work in D&D I think.

Things that happen in Thief include;

Shalebridge Cradle – you sneak through the haunted asylum, but to complete the mission you have to turn the electric lights on, then somehow sneak past all the terrifying things again, in bright light.

Ghosts – You sneak past some dumb zombies and animals, but grabbing the target means a supernatural event and oh fuck actual high level ghosts and wraiths are now patrolling about.

Rescue to Heist or Heist to Rescue – You are going in to get someone out, but can’t and end up having to re-plan to grab an item, or the opposite is true.

Guards Guards – getting in is easy but the alarms go off and now the

The entire axis of a mission might alter and now you are trying to do a very different thing, a theft becomes a rescue, an assassination becomes a theft, an exfiltration becomes a sabotage. This might be do-able in D&D.

NPC Conversations

This was one charming Thief method that sadly I could find no way to use. In Thief, guards and servants commonly mutter and complain to themselves while wandering around, they also have sometimes long, informative or just whacky conversations with each other in pairs. Just two guards chatting in the middle of the night. Coming upon these conversations and sneaking around behind them while they yap is quite charming, and listening to them often provides intel. But I couldn’t find a way to reproduce, or even use, this in D&D as long intra-NPC convo’s are a damned nightmare when the DM has to deliver the whole thing. Maybe if you are a massive ham it could be fun.

A Thief-like Dungeon

So, what do we have?

Powerful and wealthy wizards hire the PCs to do a heist. They offer to pay a LOT and have strong conditions;

· Grab this one particular thing and bring it to them.

· You don’t kill anyone or the missions off

· Ideally, you swap the thing for a fake they will give you. This raises your pay.

· Even better – no-one has any idea you were ever there. Perfect Ghosts.

· They will give you these comm-snails to help, but they don’t live long.

· They have some sketchy maps and a handful of ideas about where to get more intel.

The mission is a mansion-tower, maybe in a deep valley, or an ancient terrace mine, or somehow part sunken into the under verse. There are layers to go down, they are arranged as gardens or mazes or other somewhat-knowable patterns.

At the bottom is the mansion/tower/castle.

You have to sneak all the way down, then get inside, then sneak all the way up to get the thingy.

There will be locked doors, gates, traps and hidden problems.

There is an overwatch position somewhere where one person can see a lot of the area. If a PCs can get there and hide, they can whisper a lot of useful info to the others.

Its guarded by a clan of strong ogres. They are pretty dumb. They walk in regular patrols with lanterns. If they have a key they have it tied to their big belt with a label saying KEY, so they know what it is. The keys are also large.

There is a big gong or bell the Ogres bang on if they think something is up. There might be some kind of counter-signal or password or spell to convince them to stop this, but your patrons don’t know what it is, though it may be discoverable in the area.

There are sewers and fast-flowing water. Several of the falls, drops and traps dump you into these and will wash you up somewhere, or wash you against a grate you can climb up.

If you do get the actual treasure – surprise, it’s the only things holding the Vampire/Lich/Ghost in place. You now need to get out, but instead of, and sometimes as well as, dumb Ogres, you will now be dealing with clever, dangerous ghosts or vampires with keen senses.

I haven't played Thief but I have played a lot of the new Hitman games, which seem conceptually similar. Noting the differences -

Hitman takes place in the modern world, you are assassinating people instead of stealing from them. The ideal Silent Assassin run through a Hitman level is to kill only your targets, nobody else, and to have nobody notice any suspicious activity or find any bodies.

Shadows don't matter, sound is only mildly important. The central mechanic of the game is to knock people out and take their clothes. Once you're in disguise you're allowed access to new parts of the map (though some people can see through it.)

The ideal Hitman map is some complex social event in an exotic location, i.e. a fashion show in a mansion in Paris or a billionaire's birthday party at a winery in Argentina. It's divided into different contrasting spaces which can be accessed using different disguises. Like the winery has balconies, gardens, tasting rooms, staff corridors, vineyards, an industrial floor, a wine cellar w/ secret passage into the basement of a private house.

The idea being that you play through dozens of times and find different ways to kill your target each time. Also there's a mode which randomly selects new targets for you. So you come into a level and it seems vast and impenetrable, but over time you gradually learn all its secrets and it becomes easy to master.

-

You probably wouldn't use the "groundhog day" time loop element in D&D. Also the bit about stealing people's clothes to impersonate them is a game abstraction and clearly wouldn't work in real life, or an imaginary universe which players have to find believable.

What I do find useful though is the idea that a complex built environment can be used to organise a social structure. If that makes sense.

So like - the PCs are invited to a fancy party. There's an outer layer of guests who are just randoms, there's an inner circle who are there to engage in the real business of the event (in Paris it's a secret crime auction on the mansion's top floor.) There's a whole set of people who are just there to make the fashion show work (the models, the stylists, the kitchen staff) and all hate each other in ways which can be used to your advantage.

The structure of the mansion physically organises these people into different spaces with different energies (the cellar where the staff work is dark and quiet, the catwalk room is bright and loud, the security guys have set up a base in an attic full of dusty antiques). You have to navigate a bunch of these different spaces, both socially and physically, to get closer to your target.

Hierarchy is very important here - there's always both a social and a physical hierarchy, an "inner space" which only certain people are allowed into. In one level you literally have to be initiated into a Freemasonic secret society and get their sacred robes.

-

Setting it in the real world makes it very easy to get maps. I'm trying to write a Call of Cthulhu type game set in 1920s Blackpool at the moment. So looking at Blackpool on Google Maps - there's three piers, the sands (which would be occupied by visitors and hawkers), a huge brick theatre underneath an iron tower (with a menagerie in it), a boardwalk full of sideshow attractions, an amusement park.

Each of these can "belong" to a different set of people, and each one subdivides further into smaller spaces. Designing the game is mapping out the social dynamics, figuring out what the different characters want and how they're likely to come into conflict. Then investigating the mystery becomes mostly about exploring these social dynamics and deciding how you're going to intervene in them.

And this is one of the easiest things to describe in words. I probably gravitated towards running that type of game because it's very easy for PCs to model social dynamics - the sailor wants this, the doctor wants that, the constable wants the other thing. Might be worth making a list of things that are really easy to express in language, as well as things that are really hard.

-

I think the part about the PCs having access to flawless (telepathic?) comms and using them to co-ordinate stealth missions is really solid. The idea that even in low-fantasy games it's worth having some reason to just allow them to do it, because it opens up all sorts of gameplay possibilities that you wouldn't get otherwise.

Requires very strong spatial imagination on the part of the DM probably - you have to describe and redescribe the same physical environment from multiple angles. Or possibly if they're constantly communicating with each other you take for granted that they would synthesise their viewpoints into a sort of bird's eye view which is just represented as the map.

I received Thief: Deadly Shadows as part of a GPU bundle around 20 years ago and it was so different to anything I had played before.

Instead of cheesing your way killing sentries like you might do in an Elder Scrolls title, Thief presented the player with puzzles that could not be solved by being a murder hobo. Well, except for the odd knockout here and there.

For the first time I had to listen for footsteps, observe patrol patterns and time a sneaky entrance to purloin loot.

And there were different arrow types to manipulate the environment like water arrows for extinguishing fires/lanterns.

Now that's a franchise I should revisit.

Thanks for the detailed report!